You can help urge the Los Angeles City Council to designate the site of the Tuna Canyon Detention Station as a Historic Cultural Mounment by signing the petition. For more information and to sign, go to Change.org

LOS ANGELES — On June 8, the Manzanar Committee announced their support of efforts by the Historic Tuna Canyon Detention Station Coalition, and Los Angeles City Council member Richard Alarcon, to designate the site of the former Tuna Canyon Detention Station as a Historical Cultural Monument.

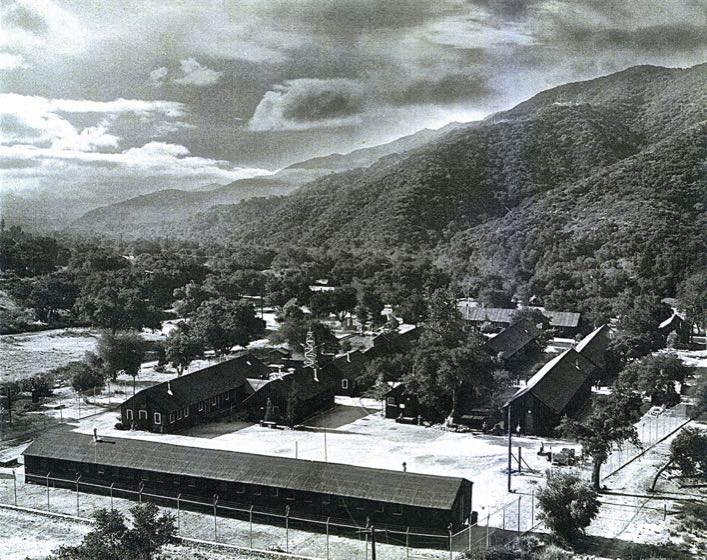

Tuna Canyon, located in Tujunga (Northeast San Fernando Valley), originally a Civilian Conservation Corps camp, became a high security prison within days after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. 1,490 Issei (first generation Japanese Americans; immigrants from Japan who had been prevented from becoming United States citizens by racist laws) were unjustly incarcerated at Tuna Canyon prior to being moved to one of the permanent confinement sites operated by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) or the Department of Justice/Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) during World War II.

Over 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, more than two-thirds native-born American citizens, were unjustly incarcerated in ten American concentration camps, along with other confinement sites, during World War II. More than 2,500 people, primarily Japanese Americans, but also Germans, Italians and Japanese Peruvians, were incarcerated behind the barbed wire fences and armed watch towers at Tuna Canyon, before being moved to other confinement sites.

Indeed, like the ten American concentration camps operated by the WRA, Tuna Canyon had the same barbed wire and watch towers armed with machine guns.

The site of the Tuna Canyon Detention Station must be designated as a Historic-Cultural Monument by the City of Los Angeles in order to ensure that a portion of the land will be set aside to commemorate the site, and to interpret its history for educational purposes.

“Tuna Canyon Detention Station should not become another lost opportunity where a vital part of American History is paved over and forgotten,” noted Manzanar Committee Co-Chair Bruce Embrey. “While our country, and the Japanese American community, have made strides in commemorating and preserving much of our history, especially the ten WRA sites, the entire story of the forced removal and incarceration of our community remains to be told.”

“This is particularly true of the Department of Justice/INS detention camps and prisons, like Tuna Canyon,” added Embrey. “Many of the WRA sites were constructed, very consciously, in remote, desolate areas, including Manzanar. Tuna Canyon, where many Japanese American community leaders and prominent businessmen were incarcerated, is here in Los Angeles, not more than a stones throw from where many Japanese Americans live today. It provides a unique opportunity to preserve an important part of our local heritage.”

“With the buildings and fences gone, it is easy to forget what happened. Regardless, or maybe even in spite of, the physical structures being gone, it is imperative that a marker or plaque, along with other commemorative improvements, noting what once took place there, be installed.”

Embrey noted that the Manzanar concentration camp was also built on land once owned by the City of Los Angeles.

“Many are unaware that the site of the Manzanar concentration camp was leased to the United States Government during World War II by the City of Los Angeles, which owned the land the camp was built on,” said Embrey. “The City owns huge swaths of land in the Owens Valley and the Eastern Sierra to protect its primary water source, the Owens River, its tributaries, and wells throughout the region.”

“When the legislation to create the Manzanar National Historic Site was introduced in Congress by Representative Mel Levine, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (DWP) vehemently opposed it, claiming that it would somehow threaten their water rights in the area,” Embrey added. “It took intervention by then-Mayor Tom Bradley and the Los Angeles City Council to overcome DWP’s stiff opposition.”

Embrey also pointed to the Santa Anita race track in Arcadia, California, which was one of the Assembly Centers where Japanese Americans were temporarily incarcerated before being shipped off to the permanent camps during World War II, as an example that the City of Los Angeles and the landowner/developer at Tuna Canyon should look at as a model.

“Santa Anita has done an excellent job of retelling what took place there during World War II without any physical alteration to the race track,” Embrey noted. “It would be a travesty of justice if the Los Angeles City Council fails to recognize the importance of this site, not just to Japanese Americans, but to the history and the people of the City of Los Angeles, and the surrounding metropolitan area, not to mention California and our nation.”

“We join with the Japanese American Citizens League – Pacific Southwest District, Nikkei For Civil Rights and Redress, and the Historic Tuna Canyon Detention Station Coalition, in urging the Los Angeles City Council to recognize the injustices done at the site of the Tuna Canyon Detention Station by designating it as a Historic-Cultural Monument, just like they did for Manzanar, located more than 200 miles outside the City limits, in September 1976,” said Embrey. “Only in this manner can we ensure that what happened at Tuna Canyon will never be forgotten, and remind us all that it must never happen to anyone ever again.”

-30-

LEAD PHOTO: Overhead view of the Tuna Canyon Detention Station Photo: M.H. Scott, Officer In Charge, Tuna Canyon Detention Station. Courtesy David Scott and the Little Landers Historical Society.

The Manzanar Committee is dedicated to educating and raising public awareness about the incarceration and violation of civil rights of persons of Japanese ancestry during World War II and to the continuing struggle of all peoples when Constitutional rights are in danger. A non-profit organization that has sponsored the annual Manzanar Pilgrimage since 1969, along with other educational programs, the Manzanar Committee has also played a key role in the establishment and continued development of the Manzanar National Historic Site. You can also follow the Manzanar Commitee on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and YouTube.

Watch the Historic Tuna Canyon Detention Station Coalition’s video

The Manzanar Committee’s Official web site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. You may copy, distribute and/or transmit any story or audio content published on this site under the terms of this license, but only if proper attribution is indicated. The full name of the author and a link back to the original article on this site are required. Photographs, graphic images, and other content not specified are subject to additional restrictions. Additional information is available at: Manzanar Committee Official web site – Licensing and Copyright Information.

The Manzanar Committee’s Official web site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. You may copy, distribute and/or transmit any story or audio content published on this site under the terms of this license, but only if proper attribution is indicated. The full name of the author and a link back to the original article on this site are required. Photographs, graphic images, and other content not specified are subject to additional restrictions. Additional information is available at: Manzanar Committee Official web site – Licensing and Copyright Information.

The actual Manzanar plaque was put in place at Manzanar on April 14, 1973. Very strong statement written for the designation of the monument at Tuna Canyon.

Yes, the plaque you’re referring to is the California State Historical Landmark plaque. The City of Los Angeles made their own, separate designation of Historic Cultural Monument status on September 15, 1976.

My maternal grandfather, Shiro Fujioka, was imprisoned at Tuna Canyon. In his translated book, Ayumi no Ato, Following the Footsteps, he wrote: